Abdominal injuries are common with children. In fact, one in 10,000 children in the United States suffer abdominal trauma every year, including 8,000 who are hospitalized for spleen or liver injuries and another 800 for damage to a kidney or the pancreas.

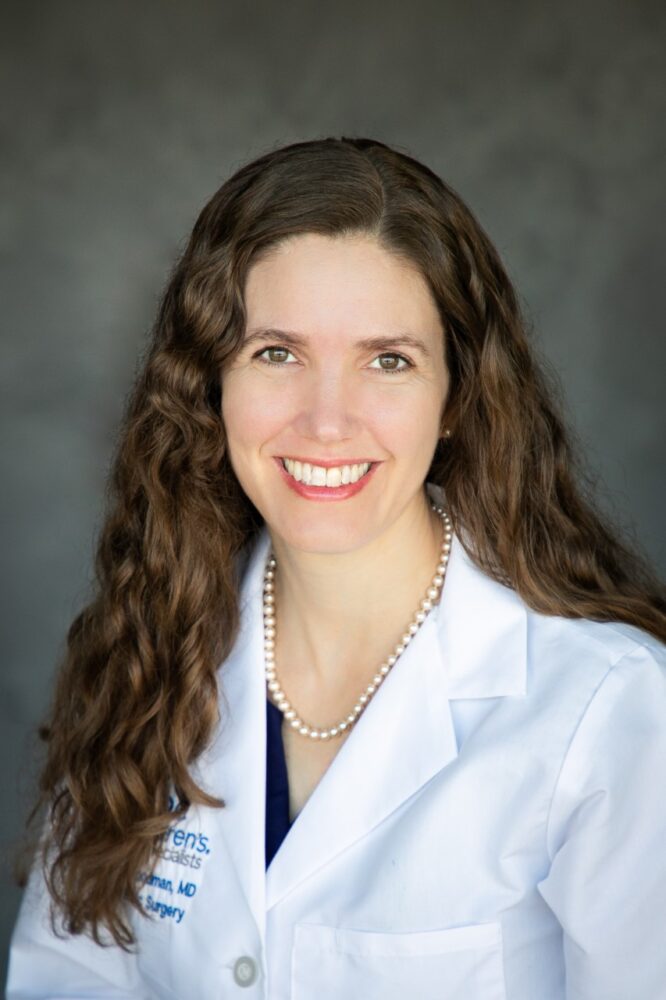

As Dr. Laura Goodman noted in her recent talk at CHOC’s Grand Rounds, doctors often see young patients with these types of injuries.

Dr. Goodman, a board-certified pediatric general and thoracic surgeon, said abdominal injuries account for about 10% of all injuries in children. They are the third most common cause of traumatic death for young people.

But, she says, there are ways to improve these outcomes.

Preventable pediatric trauma deaths: Opportunities for improvement

“One point that is really important is that a lot of pediatric trauma deaths are preventable,” Dr. Goodman says.

She cited reports that concluded around 20% of these deaths are preventable, with more than half occurring in the hospital or post-hospitalization. The data on management without surgery are clear, and often children are watched in the hospital for a short time while they recover. However, doctors are still working to determine if hospital stays can be shortened and lab testing reduced, she adds.

“The multiple questions have not yet been answered,” Dr. Goodman says. “People are still doing a lot of work in this area to figure out what the optimal care is” to reduce hospital stays and reduce activity restrictions.

About 80% of pediatric trauma in the United States are due to blunt impact, with only 7% caused by penetrating injury (e.g. stab, impalement, gunshot). The most common cause of blunt abdominal injury is unintentional falls, but the types of injuries depend on the age of the patient. Car accidents barely crack the top 10 causes of nonfatal visits to the emergency department until the five-to-nine-year-old group.

Dr. Goodman mentioned that the leading cause of death from injuries in children is now from firearms.

“I’m not going to go into that today, but it’s a very important topic that we will hopefully cover at a later grand rounds,” she says.

Accessibility to adequate medical care for young trauma victims

As far as treating patients, Dr. Goodman said that many young trauma victims face challenges in access to adequate medical care. According to the U.S. Government Accountability office, only seven states have 70 to 100% of children living within 30 miles of a high-level pediatric trauma center. More than 17 million children could not reach such a center within one hour, even by air travel.

“That means there are a lot of ER physicians, pediatricians and others are taking care of injured kids in non-trauma centers or centers that may not be prepared to take care of children,” Dr. Goodman says.

CHOC is in a minority of hospitals that are Level 1 verified for children’s surgery and Level 1 verified for pediatric trauma. In the years since CHOC first became a trauma center in 2015, and a level 1 center in 2021, the number of injured patients treated at CHOC has been increasing every year. CHOC has been receiving 20% of trauma patients as transfers from outside hospitals. In the past year, CHOC treated over 830 trauma patients.

“We’re on track to have even more that that this year,” she says.

Grading and managing solid organ injuries in children

The first priority for new patients is to stabilize them, before determining the extent of the injuries. This involves following protocols that focus on airway, breathing, circulation, and disability with interventions where needed. This is followed by a head-to-toe exam, and sometimes x-rays or CT scans. However, CHOC Trauma tries to minimize using radiation on young people because of a small future risk of malignancies. Very few children require a trip to the operating room for blunt abdominal injuries.

An interesting statistic Dr. Goodman mentioned was that mortality from spleen and liver injury decreased in recent decades, while at the same time, the number of operations also declined.

“As a surgeon to look at this, it is interesting that the less we did surgery, the better the kids did,” Dr. Goodman says. “And these are significant declines.”

Fewer than 400 children have their spleens removed in the United States every year. But when keeping the organ in place, doctors must ensure it remains healthy. Patients who keep their spleen have a 95% chance of a successful outcome.

“If we don’t take out their spleen, they have to be followed for a little while,” she says. “We have to make sure they’re doing OK.”

One of the most important parts of understanding solid organ injury is grading the injury. This can be accompanied by imaging or surgery. But, determining whether treatment in a regular hospital room or ICU are necessary do not rely on the grade of the injury any more. Instead, Dr. Goodman noted, doctors should look at the clinical status of the patient. However, there is currently inadequate data available on activity restrictions placed on the patient.

Treatment strategies and discharge instructions for liver and spleen injuries

“The safest recommendation that we have for blunt liver and spleen injury is to restrict activity, that is, full-contact competitive sports for the CT grade of the injury, plus two weeks,” she says.

Patients healthy enough to be sent home, are given discharge instructions. If children experience increased pain, dizziness, vomiting or other symptoms, they should be brought back to the emergency department.

Dr. Goodman argued against removing the spleen unless absolutely necessary. While post-surgery infections are rare, they can be fatal. Those who do receive a splenectomy should receive various vaccines and antibiotics at the appropriate intervals for the rest of their lives.

“The main point is that any kid who’s had a splenectomy should be on penicillin, at least up till age five,” she says. “Once they reach age five, if they’ve been vaccinated for strep pneumococcus and they have no history of the pneumococcal infection, then the antibiotics can be stopped.”

For liver injuries, Dr. Goodman used the example of a teenager who fell off their bike and landed on their right side. A CT scan showed a liver laceration, but their condition was determined by additional factors.

“We’re going to base our management on the patient’s vital signs and hemoglobin – their clinical status as a whole,” she says. “And then, even for a high-grade injury, once they are stable in terms of vital signs, have stable hemoglobin, are tolerating a diet and have minimal pain, we let them go home.”

The patient returned several weeks later after a period of activity restrictions. An ultrasound showed fluid near the liver, which was treated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and drainage of the fluid. Such complications only occur 3% to 5% of the time.

Reimaging is usually not required for liver or spleen injuries.

“One, complications after the injury are very rare” Dr. Goodman says. “And two, it doesn’t necessarily tell us if the organ has healed or not.”

Ensuring patient readiness for discharge and promoting injury prevention

Another example was of the handlebars of a bicycle poking into the stomach of a child as they fell. Tests showed an injured pancreas, something Dr. Goodman called troublesome because doctors are often unsure how to treat them and they can often be misdiagnosed or missed by CT scans.

Dr. Goodman stressed the importance of checking for pancreatic injury after a blunt injury to the abdomen, like the child who fell into her handlebars.

“It’s just really important to keep in mind that these handlebar injuries can be more than they seem,” she says.

Nonoperative management of pancreatic injuries were successful 96% of the time for low-grade injuries and 89% for higher-grade injuries. Complications can include pseudocysts, which occur in about 60% of patients with Grade-3 or higher injury.

“The complication rates are low, but pancreatic injuries are managed best in pediatric trauma centers for this reason,” she says. “Pancreatic injuries can be very serious.”

“We don’t discharge patients until they’re ready,” Dr. Goodman says. “That’s based on symptom improvement, not on labs and imaging.”

Dr. Goodman then talked about kidney injuries, which are less common than spleen or liver injuries. The vast majority of them – even high-grade injuries – are managed non-operatively. But patients with kidney injury can develop hypertension, so routine blood-pressure checks are important.

She concluded her talk by encouraging injury prevention, promoting education about the use of helmets and preventing window falls.

“This is really one of the most important roles for a Level 1 pediatric trauma center is helping to prevent the injuries before they happen,” she says.

Learn more about emergency and trauma services at CHOC