Numerous congenital heart defects involve right ventricular outflow tract anomalies, eventually necessitating pulmonary valve replacement for many patients. Typically, this process has involved shunts and/or conduit replacement of graduated sizes, culminating in an adult-sized pulmonary valve. The process is essential to send blood to the lungs but can involve several procedures — and frequently open-heart surgery — for the child.

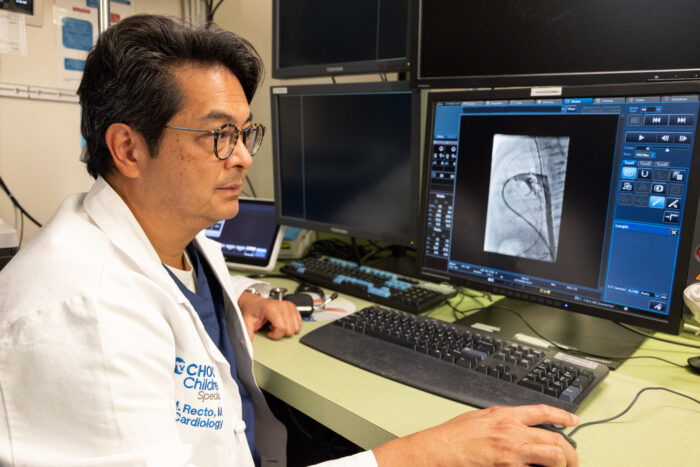

Dr. Michael Recto, medical director of the cardiac catheterization laboratories at the CHOC Heart Institute, is deeply invested in the development of a pulmonary valve for young patients who otherwise would require open heart surgery to place a new pulmonary valve. In his 27-year career as a pediatric cardiologist, he’s already witnessed the development of two transcatheter pulmonary valves, the Melody valve from Medtronic and the SAPIEN valve from Edwards.

Both are well-established for larger patients, but the valve size and delivery catheter restrict them from being used in younger patients who weigh less than 25 kilograms. These patients will frequently require open heart surgery to place a valved right ventricle to pulmonary artery conduit as a bridge to eventually getting a transcatheter pulmonary valve when they are older (at least 25 kilograms.).

Therefore, he’s teamed up with Dr. Arash Kheradvar (biomedical engineering) from the University of California, Irvine, to develop a new, balloon expandable valve, known as the IRIS Valve, that can be implanted in patients at a young age (weight of 8-10 kilograms.) with a minimum diameter of 12 millimeters that can be expanded up to 20 millimeters in diameter as the patient grows.

“Our impetus is to help pediatric patients with tetralogy of Fallot, pulmonary atresia or truncus arteriosus in the 8-to-20-kilogram range who need a new pulmonary valve who otherwise would have required surgical placement of a valve,” Dr. Recto says.

The IRIS Valve promises to help patients forgo open heart surgery and multiple surgical procedures.

“Patients who require a transcatheter pulmonary valve are primarily patients with tetralogy of Fallot that has been repaired and who now have developed significant pulmonary insufficiency (leaking pulmonary valve),” Dr. Recto says. “[Candidates also include] patients with truncus arteriosus who have outgrown conduits from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery, patients who had pulmonary atresia who underwent balloon dilation and eventually developed pulmonary valve insufficiency, and patients with pulmonary valve stenosis who have leaking valves. Any of these patients would be candidates to get this valve.”

Without the IRIS Valve, he says, many of these patients would mostly have to have open heart surgery, in which surgeons would place a surgical valved conduit between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery.

Building a better valve

Sheath size — the width of the delivery catheter to deliver the transcatheter pulmonary valve — has been the main reason very young patients cannot receive transcatheter valves via the femoral venous approach. Delivery sheaths for the Melody (22 French) and SAPIEN (24 French) valves are suitable for patients 25 kilograms or larger — about 55 pounds, or roughly the size of a child in elementary school. But by then, the child has already been living in a compromised state for years.

“That’s the main thing,” Dr. Recto says. “If you can implant this valve in patients who are younger, they’re able to live a more normal life … you would be sparing them from at least one major open-heart surgery if not more. If your pulmonary valve is leaking and you’re fatigued, you might not be as active, and your right ventricle (pumping chamber) could enlarge, and its function could deteriorate over time.”

To achieve earlier valve implantation by interventional means, Dr. Recto and his team needed to design a delivery catheter about half the size of the ones currently in use. The IRIS Valve is delivered through a 12-Fr delivery catheter and can accommodate a valve that can first be opened up to 12 millimeters and can then further expanded to 20 millimeters in diameter.

‘The valve grows as the child grows’

Not only is the IRIS Valve small enough to be delivered via a much smaller sheath than other currently available valves, but it’s built to expand. Delivered at 12 millimeters, it can be expanded up to a width of up to 20 millimeters through transcatheter balloon dilation procedures. Its valve origami design allows it to retain its three-leaflet formation at 12 millimeters and up to 20 millimeters in diameter.

“My partner, Dr. Arash Kheradvar, in charge of the Kheradvar Research Group at UC Irvine, had been working on [the origami] concept for another type of valve for adults,” Dr. Recto says. “We modified that where the valve leaflets are a little bit longer when you implant it into a 12-millimeter valve annulus and as you stretch the valve to make it bigger, the leaflets become shorter and more taut. It must work at 12 millimeters in diameter and when it’s fully expanded to 20 millimeters in diameter.”

Developed with funding from a National Institutes of Health grant, the IRIS Valve has been successfully implanted and dilated from 12 millimeters to 16 millimeters in animal models. The next steps, Dr. Recto says, may include identifying an industry partner to refine design and materials, performing further bench testing and moving into human studies within the next year.

“There’s now hope that patients [with right ventricular outflow tract anomalies] won’t have to wait until they are older to get a transcatheter pulmonary valve,” Dr. Recto says. “Instead of being in their teen years, patients as young as 2 years old may be able to get a valve without the need for open-heart surgery. If you can avoid open heart surgery, then why not try to?”

CHOC and UCLA Health together have been ranked among the top children’s hospitals in the nation for Cardiology & Heart Surgery by U.S. News & World Report.