Oliver Marley’s life was brief but very full.

Born with one of the rarest of diseases that interferes with vital cellular growth, Oliver visited Legoland with his parents and older brother, Charlie. He went on a 10-hour road trip, enjoyed the park often, and spent time around other kids.

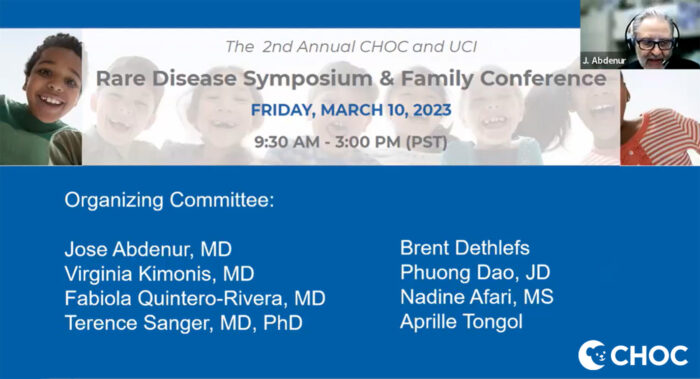

Midway through the online second-annual CHOC and UCI Rare Disease Symposium & Family Conference on March 10, 2023, Oliver’s mother, Caroline Sheehan, shared her family’s journey living with a rare disease – a reality that, while often unspoken, was at the heart of every presenter’s presentation.

“At the end of the day, let’s not forget the patients and their families,” said Dr. Jose E. Abdenur, chief of CHOC’s Division of Metabolic Disorders and director of the Metabolic Laboratory, who cohosted the symposium with Dr. Virginia Kimonis of UCI Health.

The annual event was created after CHOC and the UCI Health were designated in November 2021 a Rare Disease Center of Excellence by the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) (click here to read coverage of last year’s rare disease symposium).

Dr. Kimonis, aprofessor in the Division of Genetic and Genomic Medicine in the Department of Pediatrics, Neurology and Pathology at UCI, shares with Dr. Abdenur lead duties of the combined CHOC/UCI NORD Center of Excellence.

The designation highlights CHOC’s emergence as a growing pediatrics leader in rare disease in the clinical genetics field. CHOC now is part of a highly select group of 31 medical centers seeking to expand access and advance care and research for rare disease patients in the United States.

After enduring a month of few answers and little hope following Oliver’s birth in July 2020, Caroline and her husband, Ted, started getting answers after their newborn was transferred to CHOC.

What they heard wasn’t good.

After undergoing rapid whole genome sequencing, Oliver was diagnosed with S-AdenosylHomocysteine Hydrolase (SAHH) deficiency, an extremely rare condition with less than 30 patients reported in the world.

The disease, which affects brain, muscle and liver development, is associated with high blood levels of methionine and extremely high levels of toxic S-AdenosylHomocysteine (SAH).

Despite undergoing a tracheotomy and using a ventilator, Oliver lived a happy life before dying six days before his first birthday of a heart attack while awaiting a liver transplant.

“It was so heartbreaking, but I would never change having Oliver the way that he was – I would not change his life,” Caroline said during her presentation. “He had a beautiful life,” Caroline said. “He was a very happy baby. He touched everyone’s hearts.

“As heartbreaking as it was to lose him as young as he was, I don’t feel cheated because he lived this amazing life. And to us, he went home to be with Jesus and he is free of his disease, but we live on for him and we share his story as I’m doing now.”

No FDA-approved treatment for vast majority of rare diseases

More than 400 people from around the world registered – rare disease advocates, nurses, genetic counselors, policy experts researchers, clinicians, students, and the like – registered for this year’s symposium.

The virtual seminar was held less than a week after national Rare Disease Day on Feb. 28.

It featured a grand rounds session at 8 a.m. on March 8 with speaker Curtis R. Coughlin II from the Department of Pediatrics and the Center for Bioethics and Humanities at Children’s Hospital Colorado.

His research focuses on inborn errors of metabolism that result in neurologic dysfunction.

There are about 7,000 known rare diseases. A rare disease is defined as one affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. Most rare diseases are genetic. More than 90 percent of rare diseases are without an FDA-approved treatment.

“This is a big effort,” Dr. Abdenur said in opening remarks. “Our NORD designation recognizes the work both of our institutions have done over the years, but we take it more as a challenge and a commitment to continue doing better and to increase cooperation between our institutions and other institutions working on rare diseases.”

Several CHOC presenters

Dr. Mark Walters, apediatric hematologist-oncologist and bone marrow transplant specialist at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in Oakland, kicked off the clinical presentations with a talk on “Rare Disease & Hematology: Curative Therapies for Hemoglobin Disorders.”

There have been encouraging advances in gene therapy that someday could offer hope for patients whose main option now is an organ transplant, Dr. Walters said.

CHOC’s Dr. Diane Nugent presented on “Rare Diseases and Hematology: Rare Bleeding and Clotting Factor Deficiencies.”

“Physicians who are hematologists are so excited about gene therapy and the work that Mark is doing because most of the diseases we treat are monogenic diseases – ones that evolve from a single gene variant or mutation,” said Dr. Nugent, chief of the Division of Hematology at CHOC and clinical professor, Department of Pediatrics, at UCI, as well as principal investigator of the Region IX MCHB Hemophilia Treatment Program.

Dr. Nugent’s noted that the journey for patients to get diagnosed with rare diseases is very complicated. Many patients see several specialists who can’t diagnose them.

“A lot of our methods of diagnosing are inadequate,” Dr. Nugent said. “Oftentimes, they are not sensitive enough or because of reagents we miss defects in protein activity and genes that in your body that are quite significant.”

Technology to sequence the whole genome has helped in this regard, but “that’s a lot of data and curating it and annotating it has been a big challenge,” Dr. Nugent said.

The field of genomics is beginning to help clinicians understand that some gene variants in fact don’t cause a disease, but can make a mild gene defect become even worse .

“We call these modifying variants,” Dr. Nugent said. “We’re beginning to identify these modifying genes, which are important to know about.”

Deep Brain Stimulation

Dr. Terence Sanger, chief scientific officer at CHOC, presented on “Rare Diseases and Neurology: Deep Brain Stimulation for Treatment of Movement Disorders in Children.”

The professor of electrical engineering and computer science at the UCI Samueli School of Engineering and vice chair for research, Department of Pediatrics, at the UCI School of Medicine conducts a lot of research into dystonia and treats it with Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS).

“Until we have cures for these disorders, symptomatic treatment is all we can do, and that involves looking at the function of the brain,” said Dr. Sanger, who is trying to understand information processing in the brain and what goes wrong with it and how to make it work better – “even if we can’t fix the underlying problem.”

One problem is doctors don’t know what part of brain dystonia comes from, Dr. Sanger said.

No two children are exactly the same, added Dr. Sanger, who focuses on customizing DBS treatment to each patient in a procedure borrowed from epilepsy in which electrodes are inserted into the brain.

“We use electrical stimulation to modify the activity of the brain,” Dr. Sanger explained. “For one week, we stimulate in different places then put in permanent electrodes. We’re not fixing the brain – we’re modulating the ability of areas of the brain to communicate effectively.”

Dr. Sanger said he and his team so far have treated 41 kids and 95-96% of them have shown some improvement.

Multi-center infantile spasm study

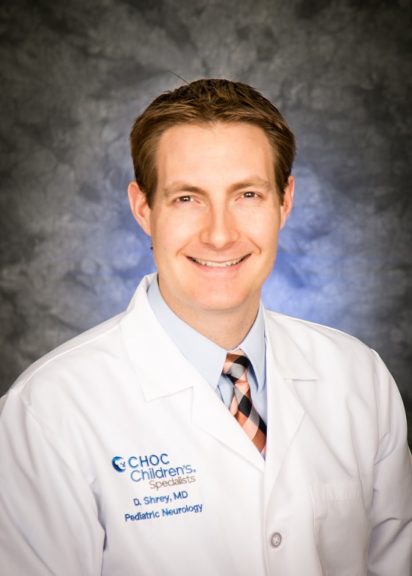

CHOC pediatric neurologist Dr. Daniel W. Shrey, an assistant clinical professor at UCI, presented on “Rare Diseases and Neurology: Using Computational Phenotyping to Improve the Management of Infantile Spasms and Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome.”

Infantile Spasms and Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome are two types of epilepsy that affect children, and every child is different and a personalized approach to treatment can lead to better outcomes, said Dr. Shrey, who is leading a 21-center study to find predictive biomarkers for infantile spasms, a rare and dangerous type of epileptic seizure that typically starts in babies 4-7 months of age.

In addition to visual analysis, Dr. Shrey uses computational EEG analysis to measure brain waves.

“It’s critical to have a large sample size,” Dr. Shrey said of the 21-center study he’s leading, which involves collecting data from 600 children nationwide. “How do we solve this problem? We form multi-site regional collaborations. This accelerates the research.”

Collaboration in National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD)

Other rare disease symposium speakers included Marybeth McAfee, associate director, Centers of Excellence at NORD, and her colleague, Corinne Alberts, NORD’s associate director for policy.

NORD, which is approaching its 40th year, hopes to accelerate research into rare diseases through its centers of excellence. Regular working groups address key unmet needs, conduct research, and educate more than 250 working group members

Scott Younger, director, Disease Gene Engineering, Genomic Medicine Center and an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Missouri-Kansas School for Medicine, presented on “New Treatments for Rare Neurological Diseases: Personalized Antisense Oligonucleotides for the Treatment of Rare Diseases,”

Dr. Albert LaSpada, associate dean for research development at the UCI School of Medicine and director of the UCI Institute for Neurotherapeutics, spoke on “Research and Innovation in New ASO Treatments for Spinal Cerebellar Ataxia Type 7.”

Never the same

Oliver’s mother said living with a rare disease is profoundly life changing.

“When you receive a diagnosis of a rare disease,” Caroline said, “it’s a crushing pain you will never experience unless you experience it.”

She added: “But look at yourself six months later, and you will not recognize the person you were when you first received the bad news. Because you will change. And you will learn to advocate.

“It makes a huge difference to be strong, and you will meet a community of families that will hold you up. You will develop a relationship with a medical team that probably you never thought you would have, and that will sustain you, and you will become a person that wants to continue to fight and talk and learn for your child and other children out there who are also suffering from a rare disease.” Concluded Caroline: “We will have a better tomorrow for these kids. It will happen.”

Learn more about metabolic rare disease research at CHOC