The crystalline, green-blue ocean beckoned.

Max, 5 at the time, wasn’t interested.

It was July 2021, and the Anayas – Max, his two younger brothers, Leo, 3, and Lucas, 2, along with older sister Keira, 15, and father Luis and mother Lisbeth – were vacationing in La Paz, on the Baja California peninsula.

For a kid who practically lived at the beach back home in Southern California, Max’s disinterest in dipping into the 82 F-degree waters of La Paz was alarming.

He had complained about lower back pain. His parents thought it was from the two-day drive to the coastal city in Mexico.

“After the second day of him not wanting to go to the beach,” Luis recalls, “I definitely knew something was up.”

Luis drove Max to an emergency room in Cabo San Lucas, about 125 miles south, where his blood was analyzed.

The doctor told Luis he didn’t know what was ailing Max, but that his spleen and liver were swollen. He recommended Max stay for a week for observation.

Luis had enough medical background to be concerned. He was a Navy medic attached to a Marine unit who, between his service from 2002 to 2009, twice was deployed to Afghanistan.

The Anayas cut their summer vacation short and took Max to Naval Medical Center San Diego (NMCSD).

Emergency visit to CHOC

Max had more bloodwork done at NMCSD, but doctors there thought he had a virus or was getting over one.

Max’s diagnosis remained a mystery after they later saw their pediatrician.

About a month after the trip to La Paz, when Max’s back pain had worsened and he became even more lethargic, the Anayas took him to the Julia and George Argyros Emergency Department at CHOC Hospital.

During his two-week stay, pediatric oncologist Dr. Jamie Frediani diagnosed Max with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), a rapidly growing cancer that starts in the white blood cells in bone marrow.

“It was heartbreaking,” Luis says, “the worse news I’ve ever had.”

Dr. Frediani started chemotherapy treatment on Max, who was a trooper when getting his chemotherapy port, a quarter-size reservoir through which medications go directly into a large vein.

“His energy and how he’s been dealing with all of this – my wife and I get our strength from him,” Luis says.

Oncology research studies at CHOC

During his treatment at CHOC, Max’s parents agreed to have him participate in six oncology research studies – three led by Dr. Van Huynh.

Max was getting his blood and spinal fluid evaluated routinely as part of his chemotherapy care, so his parents thought it wasn’t a big deal for some samples to be used for research.

Among pediatric and adolescent young adult cancer patients, improvements in survival have been attributed to enrollment in clinical trials. And such research can pay huge dividends for other patients down the line.

Among the research studies Max enrolled in are studies designed and facilitated through the Children’s Oncology Group and other studies are designed and led by physicians.

At CHOC, there are several studies looking at how to reduce the toxic effects of treatment including one Dr. Huynh-led study involving asparaginase, a key component of pediatric therapy for ALL that has several side effects including allergic reactions during administration.

Dr. Huynh’s study looked at whether pre-treatment with antihistamines will reduce the number of reactions seen and reduce the need to change treatment to another formulation of asparaginase.

Max also is participating in a Reducing Ethnic Disparities in Acute Leukemia (REDIAL) Consortium study led by Dr. Philip Lupo and Dr. Karen Rabin at Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, TX) of which CHOC is a participating site under the leadership of Dr. Huynh. This collaborative study, which began five years ago and is still ongoing, includes patients diagnosed with acute leukemia at pediatric centers in Texas and CHOC in California.

Hispanic children with acute leukemia don’t do as well on treatment as other non-Hispanic children. They’re more likely to experience worse therapy-related complications and have poorer overall survival than kids of other ethnicities. The REDIAL Consortium study is a large epidemiology-based study looking at many factors that might explain why differences are seen — and, importantly, identify where changes in treatment may be made to improve outcomes.

Measuring a key marker

Another study, led by CHOC’s Dr. Lilibeth Torno and Dr. Megan Gooch, will determine if a marker called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) can be measured in blood and spinal fluid to track changes in mental functions that occur during treatment for cancer.

There currently is no effective way to measure at what point in cancer treatment decreases in mental functions including memory, attention, and overall performance occur. This study is designed to use the results of blood tests and changes in mental function measured through two brief surveys and assessment to decide the best time to work closely with patients to lessen or prevent a decrease in mental functions.

Finally, Max also is participating in a project led by Dr. Huynh and Dr. Sonia Morales, one that also involves asparaginase. PEG-asparaginase is the most common form of asparaginase. Doctors can measure the level of asparaginase in blood to monitor response to treatment with PEG-asparaginase. Currently, these levels are collected at CHOC. However, not all hospitals, including hospitals outside the United States, have access to this special test.

Treatment with asparaginase can also decrease certain blood values such as antithrombin III (also known as AT3) and fibrinogen. Unlike blood asparaginase level, determined by a special test sent out to an outside lab, most hospitals have AT3 and fibrinogen level testing routinely available. This study aims to evaluate whether AT3 and fibrinogen levels can be used instead of blood asparaginase levels to evaluate a patient’s response to treatment.

Full of energy

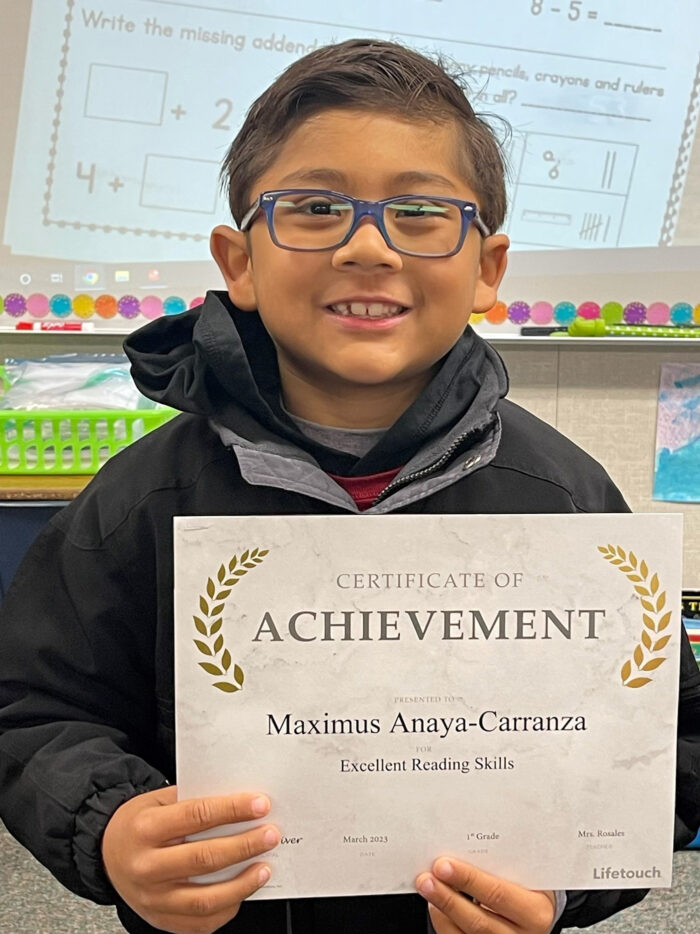

Max’s treatment is going great, his parents say.

On a recent Zoom call, the now-7-year-old was bubbling with energy.

“In December I’ll be 8,” the first grader declared.

Max was doing his homework.

“I like writing,” he said.

Max says he enjoys how CHOC treated him. He takes a pill daily at home and goes to the hospital for chemotherapy treatment every three months.

If all continues to go well, Max will get his chemotherapy port out in October.

“Since day one,” says Luis, “everyone’s been great. Everyone has treated us with respect.”

Adds Lisbeth: “All of the nurses have been great. We are super happy with the treatment Max has received.”

Max still doesn’t completely understand his condition.

Recently, he asked his father why he got sick.

“In Mexico, when he managed to go into the water once, he got hit by a wave and tossed around,” Luis says. “He thought that was the onset of all of this.”

No, it wasn’t. And hopefully soon, Max will be back celebrating at the beach.

Learn more about cancer research and clinical trials at CHOC